Is LDL really the “bad” cholesterol?

How LDL became the “bad cholesterol”

Cholesterol is an important part of human existence appearing in every human cell. Without it you would die.

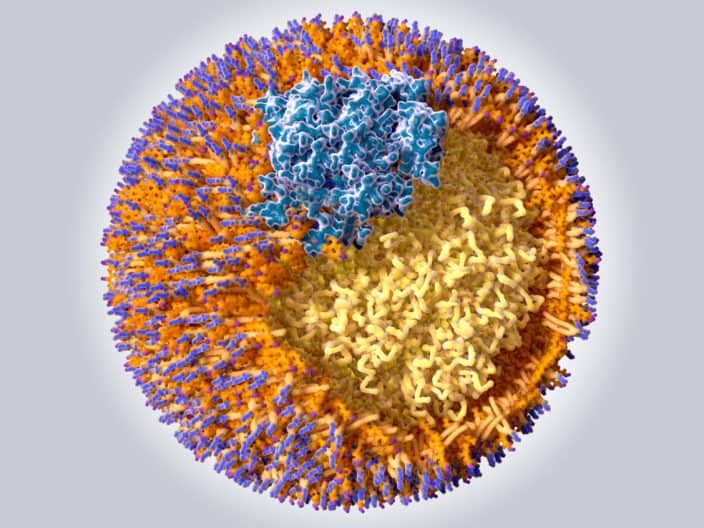

LDL (low-density lipoprotein), and HDL (high-density lipoprotein), though often referred to as “cholesterol” are, technically, carriers made of fat and protein, that transport cholesterol in the blood throughout the body. However, in common usage they are often referred to as cholesterol.

When I was child, an exceptionally long time ago, we thought all cholesterol-carrying lipoproteins were the same. Then with better testing we discovered that having more HDL was typically associated with a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and that more LDL in the blood was associated with a higher risk of CVD. Because of these correlations HDL gained the moniker of “good cholesterol” and LDL, “bad cholesterol”.

We’re now having a similar epiphany about LDL. With more advanced testing capability we’re now able to examine the subclasses (also called subfractions) of LDL in the blood and have found in an eerie “déjà vu” awakening, that just like our discovery that “all cholesterol” is not bad, the same can be said for “all LDL”.

It’s not necessarily the “bad cholesterol” after all. And the repercussions of this awakening impact many conclusions on health that were dependent on this now debunked conclusion that all LDL is bad.

A deeper look at LDL, disease, and mortality

It’s not just the controversy as to whether LDL is bad that’s been brewing in scientific coffee pot. There is growing body of evidence that discounts the importance of LDL as the sole or best determining of CVD risk.

A 2016 systematic review by an international research panel actually concluded that an analysis of 16 studies, with 30 cohorts of more than 68,000 elderly people, there was actually an inverse relationship between LDL-c and cardiovascular mortality. [ Ravnskov 2016 – International Panel ]

Studies of hospital admission records and other datasets from many epidemiological studies have also shown that LDL isn’t the great indicator of CVD risk we’ve been giving it credit for. In a recent 2019 publication, Argentine researchers at Centro de Cardiologia Nuclear in Vicente Lopez, a suburb of Buenos Aires, followed a large population of patients showing no indication of arterial blockage nor prior history of CVD at the time of initial evaluation for up to 15.9 years. They discovered that patients with LDL-c higher than 200 mg/dl (considered to be “at risk” for CVD under medical association guidance in the USA) were no more likely to experience heart attacks or angina blockage requiring mediation than those whose initial evaluation indicated serum LDL-c less than 200 mg/dl. [Pautasso 2019 – Argentina]

These recent findings following in the wake of a 2009 study by a group of researchers led by Gregg Fonarow at UCLA Medical Center, found that hospital records showed that 75% of patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease had cholesterol levels (including LDL) that would indicate they were not at high risk for a cardiovascular event based on medical association guidelines. [Sachdeva 2009 – USA]

Of course in the myopic view of the physician-researchers, this meant we should all be taking Lipitor … “just in case”. Other more open-minded observers, such as “yours truly”, view it as but another indication that LDL, without more, is at best, a weak indicator of risk.

Dozens of studies since the turn of the century have vividly shown that if we take a closer look at LDL subfractions (subclasses) we see that smaller LDL particles and in turn, a higher number of particles, have much higher association with CVD than LDL or LDL-c alone. Particle count and size are independently much better predictors of risk. [Toft-Petersen 2011 – Denmark] [Bowden 2011 USA] [Cromwell 2007 – USA] [Otvos 2011 – USA] [Mora 2014 – USA] [Wilkins 2016 – USA] [Quispe 2019 – USA].

How to adequately assess risk

Regrettably, your physician will not customarily prescribe, absent symptoms indicating a need for more, a blood test that determines any key determinants of risk other than HDL, LDL and triglycerides. Some standard lipid panels might include VSLDL concentration (very small low-density protein). And absent high-LDL, low-HDL or high-triglycerides, government and private health plans might not provide reimbursement for a more advanced lipid panel.

Since there is strong evidence that you could be at risk even if those three biomarkers were all within acceptable range, you might be left having to pay the difference in cost for a more advanced panel.

The cost of a standard panel is between US$28 and US$38 at most labs. Getting an advanced panel that shows all advanced markers, including particle count, particle size, hereditary risk markers, and inflammation markers is by way of example, US$135 at LabCorp.

Assure that your physician is aware of the science as to why these advanced lipid blood tests are necessary to assess risk. If your physician concurs that your health condition warrants the advanced test, it’s possible it would be covered by Medicare or your health plan.

Related articles:

Is eating food high in cholesterol unhealthy?

Can your negative lipid composition be reversed with diet?